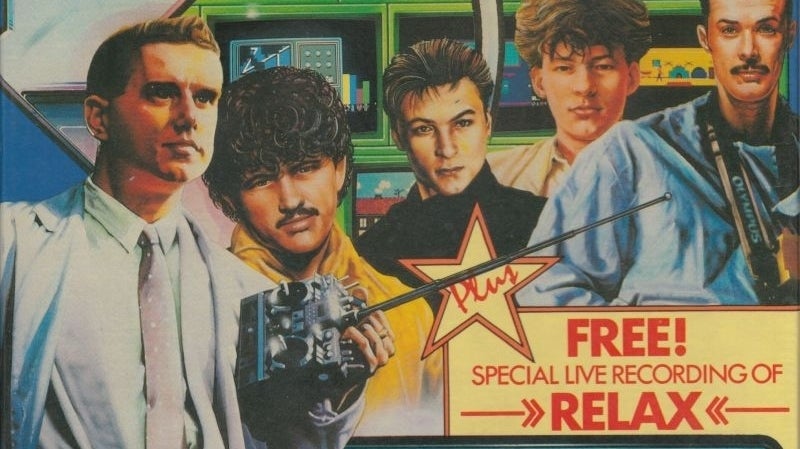

By early 1985, Liverpool pop band Frankie Goes To Hollywood could do no wrong. Having just released the fourth cut from their debut album, Welcome To The Pleasuredome in March, and with a new album incoming, the future of this stylish and overtly sexual group seemed assured. While the world of videogames was grasping the promotional power of riding on another property’s coat tails, a game focused on this most idiosyncratic of bands was hardly a natural fit. But that didn’t appear to worry Manchester software house Ocean.

At this time, Ocean was still using its favoured developers, Denton Designs, for many of its projects. Forged from the fallout of the collapse of Imagine Software the previous year, Denton Designs was swiftly establishing a reputation for original and inventive games. Everybody knew the band, and working on the Spectrum version was veteran coder John Gibson.

“[Frankie Goes To Hollywood] were famous at the time, so you’d have to have been a Martian not to have heard of them,” he says. For Liverpudlian Ally Noble, Gibson’s partner on Frankie, there was a bigger empathy for the group. “I’d seen them play at Larks in the Park in 1982,” she remembers. “They were band to see, and I slightly knew two of the members from my old art school days. We also went to the same clubs – I remember dancing with Paul Rutherford at Jody’s.”

These differing experiences inevitably influenced Gibson’s and Noble’s reactions upon hearing of the licence. “I thought David Ward [Ocean boss] was mad to want to make a game about a pop band!” exclaims the former. “Especially when the band insisted that the game didn’t have its members running around in computer form.” Super fan Ally Noble was notably more enthusiastic. “I was up for it immediately and loved the idea. While the others took a while to come round, I was very excited by the potential. I had a special affinity to the band: Liverpool isn’t a huge place, so there was a family feeling if you go to the same places.”

Denton Designs began group brainstorming, Gibson and Noble on the ZX Spectrum (and latterly, Amstrad), Graham ‘Kenny’ Everett and Karen Davies the Commodore 64, with Fred Gray on sound duties and Steve Cain overseeing both versions. “We spent a LOT of time discussing and going round in circles with ideas, again and again,” recalls Noble. “It was a hard transition, from the music into something concrete, with playability.” Help and ideas from Ocean were slim, as Gibson remembers. “It was like, ‘Go away and produce a blockbuster game.'”